País

29/09/2013 09:37:00 a.m.

- 268165″>

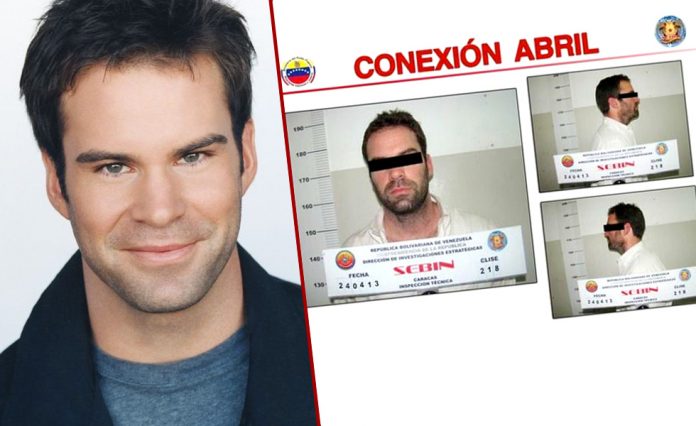

- Caracas, 29 de septiembre de 2013.- El cineasta estadounidense Tim Tracy fue arrestado el pasado 25 de abril acusado por el Gobierno de ser el contacto entre la oposición venezolana y la CIA para provocar una guerra civil en el país tras la elecciones de 14A.

Lo último que se supo de él fue su expulsión el pasado 5 de junio. Pocos días después, el joven que vino a Venezuela para hacer un documental sobre la polarización política, concedió una entrevista exclusiva a la revista Playboy para su edición de octubre.Tracy contó al reportero Mattew Ross los detalles de su detención en el Servicio Bolivariano de Inteligencia (Sebin), su traslado y estancia en El Rodeo, así como la forma en que se negoció su liberación.

“Tu trataste de matar nuestra revolución y ahora vas a morir aquí”. Con esas palabras recibieron a Tracy en El Rodeo el 29 de mayo. Lo despojaron de sus cosas que había recogido apresuradamente el día antes en El Helicoide y le dieron una franela blanca y un short amarillo chillón que le quedaba ajustado.

En El Rodeo II, Tracy vivió una experiencia que desajustó su mente. Le negaron sus medicinas para el insomnio y la ansiedad, fue humillado constantemente por el carcelero que lo condenó a muerte al llegar y confinado a una celda sin luz donde no tenía ni forma de asearse.

Una mañana fue trasladado a un pozo lleno de alimañas y excrementos, tras una conversación con su carcelero donde rechazó ser de la CIA. “La noche de su sexto día en El Rodeo, estaba temblando en otra velada de insomnio, escuchando los sonidos de la cárcel, desesperado y rascándose las múltiples picadas de zancudo en sus pies. Fue allí cuando se dio cuenta de que tal vez no vería la luz del día nunca más como hombre libre”, escribe Ross en Playboy

El periodista describe a Tracy como un muchacho un poco desorientado en qué hacer con su vida, pero señala que el comentario de una venezolana que conoció en una boda de un amigo, lo inspiró a venir al país para hacer un documental “acerca de la injusticia en Venezuela y contarlo al mundo”.

Con esa intención llegó a Caracas en 2010 y estuvo dos semanas grabando. Entrevistó a Humberto López, el popular personaje chavista que imita con su apariencia al Ché Guevara. Hizo contactos para visitar a los colectivos del 23 de Enero y en 2012, ante la efervescencia de las presidenciales de octubre, un amigo venezolano le dijo que era el momento ideal para hacer su documental.

“Tim pasó más de siete meses grabando en los más peligrosos barrios de Caracas (…) con una cámara de $20.000 sobre sus hombros, y nunca le ocurrió nada”, dice Ross en su reportaje.

Pese a que en dos ocasiones había sido arrestado y liberado rápidamente. Tracy decidió permanecer en el país. Sin embargo, cuando un grupo de funcionarios del Sebin lo detuvo en Maiquetía al intentar salir del país el 25 de abril, sabía que las cosas habían cambiado.

Su estancia en El Helicoide no la recuerda con tanta amargura como los días que pasó en El Rodeo. Allí un preso ruso, traficante de éctasis, le cambió un iPod por clases de ping pong. “Si pierdes la esperanza en una situación como esta, caes en la oscuridad”, escribió en su diario.

El final del presidio de Tracy llegó tan sorpresivo como su detención. Un día lo sacaron de su celda en el Rodeo, le hicieron un examen médico y le devolvieron algunas cosas. El país se enteró de su expulsión con un tuit del ministro de Interior, Justicia y Paz, Miguel Rodríguez.

Relata el reportaje, producto de dos días de conversación, que unas horas después de que Tracy aterrizaba en Miami, el secretario de Estado estadounidense John Kerry y ministro de Exteriores Elías Jaua, se reunían en Guatemala. El congresista retirado Bill Delahunt, había logrado la libertad del cineasta a cambio de asegurar la cita entre los cancilleres.

Mientras se recupera de su experiencia en una de las cárceles más violentas del mundo, el documental de Tracy no se detiene. Espera terminar de editar en un año y presentarlo en el festival de cine independiente Sundance 2015.

- http://www.notitarde.com/Pais/Estadounidense-acusado-de-espia-cuenta-su-experiencia-en-El-Rodeo/2013/09/29/268165

- Artículo completo:

-

INSIDE EL RODEO

by Matthew Ross

- SEPTEMBER 20, 2013 : 06:0

- On April 24, 2013, Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro ordered the arrest of American filmmaker Tim Tracy in Caracas on terrorism and spying charges. Tracy was sent to one of the most violent prisons on earth. Was he a spy? Would he get out alive?

- JUNE 4, 2013

Even if he somehow figured out a way to tune out the death threats that had been coming at him from an entire cell block of hardened killers—“You’re going to die tonight, you gringo faggot cocksucker!”—there was still no chance of sleep.

His feet were so ravaged by mosquito bites they’d begun to bleed. There were crevices in the wall on either end of his bed; the moment he lay down, endless columns of roaches came streaming out of the crumbling concrete for a well-coordinated assault on his orifices. Maybe they’d be less aggressive if he wasn’t so ripe. There was a showerhead in his cell, but its handle was conspicuously absent, and he hadn’t bathed in days. He was still wearing the humiliating outfit they’d forced him to put on just before they paraded him in front of El Rodeo’s entire general population upon his arrival: a ratty white T-shirt and a pair of bright yellow cutoff sweats so undersized they might as well have been daisy dukes. His requests for a broom and access to a shower had been denied. More troubling was the fact that his meds for anxiety and insomnia, both of which were spiking, had just run out, and his repeated requests to refill them had been met with either laughter or indifference.

The fact that Tim Tracy had held up this long—42 days, to be exact—meant nothing to him now. Being the American whose arrest was personally ordered by the president of Venezuela on live national television—that Tim could handle. He’d found a lot of it amusing at the beginning, especially the armed convoys that accompanied him to and from courthouse visits. Who did they think he was, Jack Bauer?

Then the rules changed. Six days earlier, he had been transferred from his cell at the national intelligence headquarters in Caracas to El Rodeo, the most infamous prison in a country whose prison system was perhaps the world’s worst. He was no longer being used as a political pawn by a desperate government on the verge of collapse.

Now Tim Tracy had become a target.

At this particular moment, no one—not even President Nicolás Maduro—could guarantee his safety. Although the wing he was staying in, El Rodeo Dos, was supposed to be secure, the buildings on either side, Uno and Tres, were run by gang leaders. There were no prison guards, just armed thugs with AK-47s and rocket launchers. All it would take was one bribe, or one riot like the one that had happened here two years ago, and he’d be dead.

Then, out of nowhere, a pair of female nurses appeared, both young, both gorgeous, standing in front of his cell door and telling him to come with them. He couldn’t be entirely sure they were real. Was he hallucinating? A guard unlocked his door, and the two women were still there. Tracy was standing up and joining them. They were leading him down a hallway, away from the squalor of his cell. Were they taking him to a death chamber? Was he being released? He had no way of knowing. He decided to roll with it and not ask any questions.

It wouldn’t be the first time he had followed a Venezuelan girl into unfamiliar waters. If it weren’t for Alejandra, none of this would ever have happened.

CHRISTMAS WEEK, 2011

The evening began at the Chateau Marmont, the only place in Los Angeles with anything resembling old-school Hollywood glamour. I’d been in town for yet another round of casting on the independent film I’d been trying to make for way longer than I was willing to admit, and a girl had invited me to join her and some friends for dinner in the garden.

Sitting across from me was Tim Tracy, a stocky spark plug of a guy with a wildness to his eyes. He was around my age and had been hustling here for almost a decade, but he had a childlike enthusiasm uncommon to veterans of the Hollywood jungle. There was no affectation or cool-guy posturing, no faux-humble name-drops to boost his cred. He said he was a filmmaker but without the usual whose-dick-is-bigger subtext that characterizes most first-time encounters at a place like this.

There was something a little off about Tim. I got the feeling that, like me, he was unsatisfied—with his career, with everything—and he was wired in a way that necessitated some kind of outlet for all that unexpressed energy, some substitute for the insanity of making a movie. After interviewing dozens of directors over the years, I had learned that many people were drawn to movies because making them was the only thing that could calm them down. But until that happened, the challenge was figuring out where to burn off all that stockpiled energy before it got radioactive.

I discovered Tim’s preferred method a couple of hours later, when our group moved the party from the Chateau to his bungalow in Laurel Canyon. I found myself in the living room, watching as Tim scurried about the space like a man possessed—turning on stereo, strobe light and smoke machine, handing out random props (DEA vest, top hat, plastic swords). An all-night dance party commenced.

At some point Tim made a running, jumping grab for the metal chandelier hanging from the ceiling. He swung around the room before the cord snapped, sending both him and the chandelier plummeting before stopping, abruptly, a foot from the floor. Tim’s friends all laughed. They seemed to enjoy his antics as an expression of some youthful desire to connect to the world.

Was Tim living in a place far above his pay grade as a freelance TV documentary producer with a trust fund to fall back on? Absolutely. Was his Animal House shtick a little ridiculous for a guy his age? Sure. To the casual observer who was quick to judge, Tim was an easy guy to write off. But as I would soon learn, underestimating Tim’s capabilities, or his courage, would be unwise.

We became Facebook friends, and a few months later I was back in New York, thinking I would never see Tim Tracy again.

APRIL 26, 2013

The e-mail arrived as I was walking across Central Park. It was from Alanna Sampietro, an actress friend from L.A. who ran in Tim’s circle, with the subject heading: “Sign please! My filmmaker friend arrested in Venezuela.” I opened the e-mail, a form letter generated through the website Change.org. “My friend Tim Tracy has been arrested in Venezuela,” it began.

Tim Tracy from Laurel Canyon? I clicked through to discover that Tim had been arrested two days earlier at the Caracas airport on his way out of the country. When I read that Tim was in the custody of SEBIN, Venezuela’s national intelligence service, on terrorism charges, I stopped in my tracks.

I began scouring the net on my phone. Tim hadn’t been formally charged yet. Still, Venezuela’s newly elected president, Nicolás Maduro (who had recently taken office after Hugo Chávez’s death from cancer), and his interior minister, Miguel Rodríguez Torres, had held news conferences that were carried live by every major TV network in Venezuela. The interior minister announced that the country’s new presidential regime had taken down a major threat to national security: the April Connection, a secret plot whose objective was to destabilize the country through acts of violence, with the ultimate goal of starting a civil war. And though the members of this terrorist cell were right-wing ultra-capitalists who had been recruited from the ranks of Venezuela’s antigovernment opposition, the man in charge was an American: CIA field agent Timothy Hallet Tracy, an ingenious master of deception who oversaw everything from laundering cash to masterminding acts of terror, all while maintaining a cover identity as a filmmaker at work on a documentary. The reports also mentioned that he’d been arrested twice before, in October and February, for suspicious activities.

“He is trained and he knows how to infiltrate and how to handle sources and security information,” said Rodríguez Torres. “Those big powers who do this type of spying, they often use the facade of a filmmaker, documentary-maker, photographer or journalist. Because with that facade they can go anywhere, penetrate any place.”

President Maduro wasted no time in casting himself as the noble proletarian hero when he addressed the press. “The gringo who financed the violent groups has been captured,” said Maduro. “I gave the order that he be detained immediately and passed over to the attorney general’s office. Nobody can be destabilizing this country, whatever they believe, because they’re on the side of the bourgeoisie.”

The flurry of news reports about Tim included a handful of quotes from his friends and family, all of whom proclaimed his innocence. Aengus James, a producer-director who had worked with Tim, told the Associated Press, “They don’t have CIA in custody. They don’t have a journalist in custody. They have a kid with a camera.”

On April 27 Tim was formally charged with criminal conspiracy, making false statements and using a false document. He was denied bail. According to Venezuelan law, the government would be granted 45 days to prepare its case before a hearing on June 11, when the judge would rule whether to move forward with a criminal trial. No one with any knowledge of Venezuelan criminal law expected Tim to have a chance of winning a court battle, so the upcoming hearing would almost certainly determine his fate. He was facing 30 years, the maximum sentence in Venezuela.

I began to feel an immediate rush of two intense and conflicting emotions: deep concern for a man I hardly knew but who had made an impression on me, and the charged excitement of inspiration. This was a story that spoke to me powerfully but in a way I didn’t yet understand. There was also an old-fashioned mystery that needed solving: How had Tim become the Osama bin Laden of Venezuela? Was Tim Tracy a spy?

•

Tim grew up in the suburbs of Detroit. The Tracy family made its fortune in auto parts following World War II, and Emmet, Tim’s father, prided himself on the fact that he babysat Mitt Romney while Mitt’s father, George, was on the campaign trail. When Tim arrived in Connecticut for his freshman year at Hotchkiss, an upper-crust boarding school, he was hyped as one of the best eighth-grade hockey players in the country, just as his older brother Tripp had once been. But this was a hormonal coed boarding school, and the pressure of playing in front of all those chatty little girls got inside his head. He’d get in a game and freeze, crippled by the fear that if he fucked up none of the girls would talk to him. He never came close to reaching his potential. Tripp ended up playing goalie in the NHL, while Tim wasn’t even the best player on his high school team.

He never played at Georgetown, but after graduating in 2001 he joined a semi-pro beer-league team in Sun Valley, Idaho. In the team’s final game of his first season, Tim skated onto the ice Slap Shot–style wearing nothing but his skates, pads, helmet and a jockstrap, with THANKS FANS scrawled across his ass. The crowd went nuts. At the bar that night, he was a star. Everyone told him he was crazy, and he loved it. He went home with a girl named Barbie, the star of the figure-skating team—more evidence that the world tended to cooperate when he played a character and that he was better at reading other people than he was at reading himself. He figured he’d roll with it. Later that year Tim moved to L.A. to try to make it as an actor. If he could make a living by hiding, maybe he’d never have to really look at himself in the mirror.

After six years of hustling, he turned 30 and had nothing to show for his efforts save a couple of blink-and-you’ll-miss-him TV gigs. No matter how hard he worked, there was always this voice inside him saying, “This isn’t who you are. Try something else.” One night he was at a bar called the Green Door when out of nowhere an extremely hot girl sat down next to him.

“So,” she asked, “what do you do for work?”

He said it without even thinking: “I’m an active member of Delta Force.”

“Really? What’s that?”

“We go behind enemy lines and do terrorist shit,” he replied, straight-faced. “We’re very discreet. I don’t want to talk about it. I’m on leave and have to ship out tomorrow for Falluja.”

The reaction on her face was unlike anything he’d ever seen before—a combination of concern, awe, respect and desire. “Oh my God,” she said. “Thank you so much for your service to our country.” He knew what he was doing was deeply wrong, but it felt good to be in the Delta Force, even if for a moment.

She invited him back to her place. It was fantastic. When he woke up the next morning, he knew he should come clean, but he didn’t want to burst the bubble for either of them. She thinks I’m shipping off to Falluja, he said to himself. Let’s just keep it that way.

Two weeks later, he was back at the Green Door when she walked in. Eye contact, a moment of horror that eviscerated his character, and she was gone. It hit him hard. What he had done went deeper than dirtbaggery. It was inescapable proof that he had lost his way.

He quit acting and decided to learn the craft of filmmaking, to make a film that mattered. His fortunes began to change almost immediately. His friend and mentor Aengus James, also a former actor, gave him work as a producer on a documentary called American Harmony, as well as on Madhouse, a TV series about car racing for the History Channel. Tim quickly discovered that he had the natural skill set for production: effortless multitasking, obsessiveness and a preternatural ability to connect with just about anyone. What Tim needed was his own story to tell.

That opportunity first materialized in the dangerous curves of a sexy Latin girl on a dance floor. He was at the wedding of a Venezuelan college buddy when he found himself transfixed by a girl named Alejandra. The way she would put the back of her hand on the guy she was dancing with was the sexiest thing he’d ever seen.

When a Madonna song came on, Tim made his move. His Spanish was terrible, as was Alejandra’s English, but the chemistry was off the charts. They agreed to meet in Miami, where Alejandra began to tell Tim about Venezuela.

“I was on the street protesting every day,” she said. “My president is a dictator, and half of my friends were teargassed and beaten and sent to prison.”

She went on to explain that she was a member of the student opposition in Caracas that had been fighting the oppressive regime of President Hugo Chávez, who had enlisted murderers and thugs to enforce his will. She had a flair for the dramatic, and he bought all of it. He was moved by the imagery of these kids fighting for freedom, and he also had a girl to impress. Sensing an opportunity to play the hero, Tim made a fateful promise to Alejandra: He would make a film about the injustice in Venezuela and tell the world. He booked a ticket to leave in three months’ time and began tutoring himself on Venezuelan politics.

Chávez was no run-of-the-mill caudillo (Latin American military dictator); he was a supernova. Born in poverty to schoolteacher parents, he got his start in the Venezuelan military and began to fashion himself as the socialist reincarnation of Simón Bolívar, who had liberated Venezuela from Spanish rule in the early 19th century. Following a disastrous coup attempt in 1992, Chávez was imprisoned yet somehow managed to secure his release two years later, eventually seizing power in 1999 in what he called the Bolivarian Revolution. Aligning himself closely with his friend Fidel Castro, he emerged as a deceptively savvy anti-U.S. firebrand whose questionable mental stability and rumored cocaine dependency never got in the way of a camera. Every Sunday, he’d hold court on his nationally televised talk show Aló Presidente, which ran around six hours or whenever he decided to end it.

Tim was hooked. He soon found out through a friend that Alejandra was sleeping with another guy in Venezuela. It stung, but he could handle it. He was losing track of the girl. Now he had fallen in love with the country.

•

In 2010 Tim spent two weeks in Venezuela, filming rallies organized by students who didn’t quite live up to Alejandra’s billing. One lesson his friend Aengus had taught him early on was that a documentary filmmaker’s best friend was a bullshit detector, and most of these well-off kids weren’t passing the smell test. They were great at organizing rallies, but all it took was a glimpse of the chaotic shantytowns that dotted the outskirts of Caracas to see there was more to this story.

At a protest outside the Ecuadorian embassy, Tim met a local legend named Humberto Lopez who called himself Che and resembled the real Che Guevara to an astonishing degree. Che offered to take Tim for a walk through 23 de Enero, the most notorious barrio in Caracas and Chávez’s spiritual base. The moment Tim walked into the hillside shantytown built on the ruins of a public housing project, he felt the jolt of inspiration. This was a place where Chávez was considered a god—a point driven home by a massive Last Supper mural with Hugo sitting alongside Jesus—but whose inhabitants were living in squalor. How was that possible?

Tim realized that in order to make the film he wanted, he would have to go into the heart of darkness, into the barrios. That the disenfranchised could be so in awe of a leader as to make him a deity—there was the story. Tim knew he’d need a dramatic event to frame his narrative. It took two years to materialize. In September 2012, nine months after I’d met him, he was back in L.A. when he got a call from his friend Ricardo Korda in Caracas. The presidential election was a month away, and Chávez’s opponent, Henrique Capriles Radonski, was gathering steam. Chávez was politically vulnerable and suffering from a dangerous cancer, and everyone knew it. The Caracas streets buzzed with demonstrations and the occasional violent exchange between Chavistas and the opposition. Civil war was on the table.

“If you want to make this film, you need to come down here right now,” said Korda, who eventually became a co-producer on the project. “You’re never going to have another chance to do something like this. Everything is on the verge of falling apart.”

Tim grabbed his equipment and took the first flight out of L.A

•

In a city where using a cell phone on the street even in a good neighborhood is considered reckless because of rampant street crime, Tim spent most of the next seven months filming in the most dangerous barrios of Caracas, places like 23 de Enero and Catia. He did so with a $20,000 camera on his shoulder, and he never had to defend himself.

“Take the South Bronx of the 1970s, transport it to the age of crack in the 1980s, overpopulate it and throw in Fidel Castro during the revolution, and that’s 23 de Enero,” says Jon Lee Anderson, who in his 35-year career as a foreign correspondent has filed stories from the most harrowing war zones on the planet. Anderson has written extensively about Venezuela, including a portrait of present-day Caracas for The New Yorker that appeared in January, exploring the same barrios that Tim was filming at the time. “In a place like Caracas, the abnormal is normal,” says Anderson. “There were times when I was in the proximity of people who would have had no compunction to shooting me. You adopt a certain body language, you try to be inoffensive, you do this, you do that, but you also have to push it. I pushed it. Tim pushed it. It’s just what you have to do.”

To understand Venezuela, Tim needed to learn the ways of the poorer Chavistas—how they operated, the blurred lines between political activism and criminality. The fact that he didn’t speak much Spanish allowed him to learn the language in the most organic way possible, from his sources.

Tim soon discovered his affection for Venezuela was reciprocal. While gaining the trust of hard men whose leader was constantly proselytizing about the gringo devils of the USA, he found that Venezuelan girls couldn’t get enough of him. He ended up choosing a guy named Jhonny as the focus of his film. Jhonny was a member of El Frente, one of 23 de Enero’s most powerfulcolectivos, the pro-Chávez radicalized street gangs who handled law enforcement in the police-free barrios. Jhonny was also one of Caracas’s infamous motorizados, the independent motorcycle taxi drivers who weave through the city’s gridlock at breakneck speeds. A girl Tim knew once told him a story about being on the back of one of these bikes when her motorizado calmly pulled out a pistol and tapped it on the window of the car next to him. The terrified driver gave up his wallet and phone, and the motorizado sped off. At the next stoplight, the terrified girl offered up her own possessions and begged for him not to kill her. The motorizado was offended. “We have principles in Venezuela,” he said. “We never rob the customers.”

Through Jhonny, Tim hoped to gain a greater understanding of how 8 million people could have voted for a guy who, over 14 years, had squandered billions and left the country with one of the highest homicide rates in the world.

Tim’s identity was now inextricably tied up in the movie. He was spending his modest trust fund on it, and he decided to stay in the country after his first and second arrests. In both instances, he got pinched for filming images that were off-limits—first a sniper on a roof at a Chávez rally in October 2012, then the presidential palace in February 2013. In both cases he was released after three days, following some interrogation and a lot of sitting around. The police, it seemed, were far less threatening than the dwellers of the barrios where Tim was spending his days and nights.

Early in 2013, as Tim continued to shoot footage, events in Venezuela took a turn for the worse. On March 5 the charismatic president Hugo Chávez succumbed to cancer, leaving Nicolás Maduro—a former bus driver who had risen through the ranks to become Chávez’s vice president and handpicked successor—to run things. Maduro had none of his mentor’s extraordinary charisma. Despite having more oil reserves than Saudi Arabia, Venezuela was in shambles. Maduro was losing control. In order to buy himself more time, he’d need to manufacture a distraction.

•

April 24, 2013

Tim awoke after having spent the night with two senoritas, which explains why he missed a morning flight out of Caracas. He had two birthdays to attend in the U.S.: his dad’s 80th in Michigan and his close friend Sasha Bushnell’s 30th, which he’d be hosting in Laurel Canyon. To assure maximum awesomeness, he had gotten a friend to reinforce his chandelier to safely hold the swinging weight of “one full-grown male and one petite female.”

He booked himself on the next flight out. As soon as he got through immigration at Simón Bolívar International Airport, he was suddenly surrounded by a group of armed commandos, who had been waiting for him. He was handcuffed and led downstairs to a detention center. At this point he was more annoyed than frightened—he’d been through this before—but something felt off. There were a lot more guns in the room, and his every movement was monitored. Now they were fucking with his travel. He thought he could talk his way out of it.

“I’ve got a three P.M. flight that I don’t think you want me to miss,” Tim explained with exaggerated selfimportance.

“No big deal,” the supervising commando responded with a smile. “If you miss the flight we’ll just put you on a private plane and send you back.”

That’s when Tim knew something was really wrong. There was no way they were going to put him on a private plane.

He was right. That night Tim was transferred to Helicoide, a massive, pyramid-shaped structure in central Caracas that served as the headquarters for SEBIN. Upon arrival he was whisked into an interrogation room, where Elvis Ramírez—the director of Helicoide—went at him hard with accusations that he was CIA. Tim denied everything, but Ramírez could not have cared less. The next day, Maduro and Interior Minister Rodríguez Torres went on a public-relations offensive, accusing Tim on live TV of heading the April Connection.

Two days after his arrest, Tim was transported in a convoy of 20 vehicles packed with special-forces soldiers to another prison near the airport for a change-of-venue hearing. While he waited, prisoners in the adjacent cells began a horrifying chant: “Kill the gringo! Kill the gringo!” The color drained from Tim’s face, and he began to shake. When he was in the barrios filming the Chavistas, he would often hear his subjects parrot the absurd lies Chávez had fed them about the Sodom and Gomorrah that was the United States. Tim had a nickname for that brand of misinformation: “weaponizing the Kool-Aid.” The Kool-Aid had most certainly been weaponized.

•

One can only imagine the shock when the phone rang in the home of Tim Tracy’s parents back in Grosse Pointe Farms. Following the initial wave of news reports, family and friends closed ranks on the advice of Tim’s Venezuelan attorney, Daniel Rosales, who was handling “back-channel” negotiations and supervising his criminal defense. Contact with the press was prohibited for fear of provoking Maduro, who had been doubling down on his anti-Americanism.

Soon after Tim’s incarceration, President Obama went on record to say that the charges against Tim were “ridiculous.” Maduro responded by calling Obama “the grand chief of devils.” Obama’s comment hadn’t done Tim any favors, but Maduro’s crazy reply alerted the international community that Tim’s arrest was nothing but a cynical ploy by a desperate president who would resort to anything to shore up support. In other words, Tim was clearly innocent. He was no spy. Maduro had no evidence whatsoever, but he didn’t care.

Maduro’s regime was losing power by the day. By arresting Tim, he was taking a page out of his mentor’s playbook: When in trouble, unite the base against a common enemy—capitalist oppressors. Divert attention away from domestic turmoil by resurrecting the ogre of the U.S. and establishing a direct connection between the U.S. and the opposition. Maduro was portraying his administration as capable defenders of national security at a time when civil war was looking like a distinct possibility.

Various “Free Tim Tracy” movements got under way—from rumors of American celebrities including Oliver Stone and Sean Penn personally texting Maduro to a committed effort by retired congressman Bill Delahunt, who during his 14 years on Capitol Hill was known as the only U.S. politician on good terms with Chávez. Delahunt got on board with Tim’s cause thanks to the efforts of Tim’s brother Tripp, who had an old Harvard buddy whose family knew the former diplomat.

Meanwhile, the situation in Venezuela continued to unravel. The week after Tim’s arrest, a wild fistfight broke out in parliament between supporters of Maduro and the opposition, leaving men in suits bloodied and bruised. Three weeks later, the president was humiliated when a recording of a conversation between a Cuban intelligence officer and Mario Silva, the Rush Limbaugh of the Chavistas movement, was leaked to the press. Silva’s main point was summed up in the following sentence: “We are in a world of shit, my friend.” So was Tim.

•

Tim spent 36 days in Helicoide, an experience that, given the circumstances, was actually not that bad. His fellow inmates were a cast of characters worthy of a Dirty Dozen remake. There was David from El Salvador, who lent Tim his iPod in exchange for Ping-Pong lessons; Steve, a.k.a. Boris, a funloving Russian arms and ecstasy dealer; Assan, a chess champion and financier from Lebanon whose only crime was losing his passport; and Walid Makled García, a.k.a. El Arabe, who until his capture in 2011 was one of the world’s most powerful drug lords.

Tim fit in immediately and within days was holding his own in the nightly Ping-Pong tournament. He spent hours writing obsessively in his diary and taking advantage of the gym. He had faith that when judgment time came on June 11, he’d be exonerated and could go back to making his movie. If you lose hope in a situation like this, you slip into darkness, he thought to himself.

His communication with the outside world was limited to phone calls to his parents, his Venezuelan attorney and his best friend, Stone Douglass, a film producer who had somehow convinced the Venezuelan authorities that he and Tim were cousins. The stress of trying to secure Tim’s release from a government that appeared to have no regard for reality, diplomacy or justice made for tense moments back in the States. Tim’s friends, acquaintances and more than a few total strangers were trying to solicit celebrities, organize protests, launch social media campaigns and initiate other forms of public outcry. The fact that so many were trying to help was telling. It wasn’t just out of loyalty or in the interest of justice; it was because Tim had put it all on the line to tell a story that needed to be told and in so doing had transformed himself from a run-of-the-mill L.A. freelancer half a year earlier to the man he had always wanted to be. Tim wasn’t just loved by his friends—now he was something of a hero.

The darkest moments came after speaking to his parents, who were in a state of extreme anguish.I never doubted or regretted one decision I made, Tim thought to himself. I did the right thing, but was I selfish? Did I consider anybody but me?

On Tuesday, May 28, word spread that some prisoners were going to be evacuated without any explanation. Some said it was because of overcrowding, others said it was for renovations. At five the next morning, Tim and seven inmates from his “band of brothers” were awakened and told they had a few minutes to pack a shopping bag to take with them. Whatever possessions remained in the cell would be thrown out.

They were being moved to El Rodeo Dos, which SEBIN officials assured them was Venezuela’s model prison, complete with athletic facilities and staffed by corrections officers specially trained to understand the needs of foreign inmates. None of what Tim heard passed the smell test. To begin with, if it really was necessary to evacuate Helicoide, why were so many of his fellow inmates remaining behind?

This wasn’t looking good. As Tim was being led out, Steve, the Russian, pulled him aside. “I got one word of advice for you,” said Steve. “Don’t trust anybody.”

•

May 29, 2013

The moment El Rodeo came into view from his seat on the transport van, Tim knew his fears were justified. The prison entrance was riddled with bullet holes from a prisoner uprising two years earlier that had resulted in 25 deaths. The whole thing reminded him of Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome.

“Venezuela’s prisons are just about the worst on Earth, and I say that measuring every word carefully,” says Anderson. “El Rodeo has an absolutely terrible reputation. For an American to get sent there and not get hurt or killed would be highly unlikely.”

The warden, a 40-ish slob whose godmother was head of the national prison system, was waiting for Tim and the other SEBIN transplants in the processing area. He wasted no time in marking his territory. After confiscating all the prisoners’ personal items but their toothbrushes, he took out a pair of electric clippers and shaved the head of each new arrival. He lit up when it was Tim’s turn. Here was the famous gringo he’d heard so much about. The warden leaned in close.

“You tried to kill our revolution, and now you’re going to die in here,” he said. All the guards laughed.

Tim spent his entire stint at El Rodeo in solitary confinement, during which time he was subjected to taunts and various forms of humiliation by a guard named Alvaro, one of the highest-ranking corrections officers in the building. Tim took to calling him Kevin Bacon, whose prison-guard character in the film Sleepers had a similar sadistic streak. Alvaro verbally berated Tim while he defecated, wouldn’t let him bathe and confiscated his bedding and towel. On day three, as Tim was being transferred from one solitary cell to another for no apparent reason, he saw his friend Assan from Helicoide being led in the opposite direction. As the guards stopped to chat, Assan leaned and whispered to Tim.

“I heard they’re going to kill you tonight,” he said. “Be careful.”

Tim barely made it to his new cell without collapsing. He was overcome by a panic attack that left him shaking in his bed. He told the guard he needed to speak to Alvaro. When Alvaro arrived, Tim begged to see a priest so he could be issued last rites before they murdered him.

“Sorry, gringo,” Alvaro said, smiling, “we don’t do that in here.”

Tim spent the night in terror. When morning came and he was still alive, the fear was replaced with rage. Alvaro came by to talk smack about Tim being in the CIA. On this morning Tim wasn’t taking any of it. A few minutes later, he was thrown into a vermin-infested, shit-stained basement pit and left alone to drive himself mad.

On the night of his 42nd day of incarceration—his sixth night inside El Rodeo—he found himself awake and trembling, another night of insomnia, listening to the sounds of the prison, smelling its despair, scratching at the bloody mosquito bites on his feet. There was a horrifying realization—this was his existence, and it was highly possible he would never see the light of day again as a free man and would die in this Venezuelan hellhole.

The next morning, the two beautiful nurses appeared at Tim’s cell. He had no choice but to follow them. He did not know if he was following them to his death, to another cell or to his freedom. He was led to a room where a doctor gave him a medical checkup. He realized he was being released when he was given exit papers to sign and not one minute before. He was given his clothes back, the clothes he was wearing when he arrived at El Rodeo. Like his arrest, his release came quickly, without warning. Tim Tracy was set free.

•

June 5, 2013

With no evidentiary hearing, Tim was expelled from Venezuela and put on a flight to Miami. The only explanation consisted of a single tweet from Interior Minister Rodríguez Torres: “The American Timothy Hallet Tracy, who was caught spying in our country, has been expelled from the national territory.”

Tim was supposed to land in Miami and then board a connecting flight to Los Angeles, but his family intercepted him in Florida and took him to their vacation home in Palm Beach. It appeared that Tim’s homecoming wasn’t exactly smooth, that he wasn’t in the best shape mentally. By all accounts he had been a marvel of positive energy during his first month behind bars. Something must have happened inside El Rodeo.

The diplomatic savvy of retired congressman Bill Delahunt was what ultimately won Tim his freedom. In a classic quid pro quo, Delahunt managed to secure a meeting between Venezuelan foreign minister Elías José Jaua and U.S. secretary of state John Kerry in exchange for Tim’s release. A few hours after Tim landed in Miami, Kerry and Jaua were sitting down together.

Ten days later, Tim got on a plane to Los Angeles. Despite having a loyal support network in L.A., he decided to stay under the radar. Reporters had camped outside his Laurel Canyon home for days, and to avoid being spotted, Tim spent his first week in town hiding out at his friend Stone Douglass’s house in Santa Monica’s Rustic Canyon.

Tim’s older brother Tripp was the only member of the Tracy family to speak to the press about Tim’s release. Although his affection for his little brother was plainly evident as he choked back tears on camera, he began the interview with a telling description: “For anybody who’s seen the movie Spies Like Us with Chevy Chase and Dan Aykroyd,” Tripp said, “that’s about as close to a spy as Tim Tracy is.” While his intent was anything but malicious, the statement struck me as jarring, comparing the bumbling comic duo unsuited for survival in a foreign country to Tim and his ordeal in Venezuela.

I had flown to L.A. the day Tim was released and had been hanging around for two weeks when I finally got the call I’d been waiting for. It was from the crisis-management publicity expert Tim had hired after he got out, who said Tim was in town and except for me he had decided not to grant any interviews for the foreseeable future. I’d get as much time as I needed. The following morning I drove to Santa Monica.

Had I not watched a five-second video clip of Tim walking through the Caracas airport the morning he was released, I probably wouldn’t have recognized him. I knew Tim as a doughy, shaggy-haired preppy, but the guy who greeted me at the door was ripped and rocking a buzz cut. If he had suffered severe trauma in El Rodeo, as I’d been led to believe, he was hiding it pretty well.

As we sat in a garden, Tim started to talk and didn’t stop for the next two days. In many ways he was the same guy I remembered meeting but more confident and impassioned by a sense of social justice. He told me that though he’d had a couple of epic meltdowns following his release—one on the plane when he’d misplaced his passport and nearly got kicked off and one back in Palm Beach with his parents—he was now feeling like himself and focused on finishing his film, which he estimated could take a year to edit. (He hopes to have it ready for Sundance in 2015.) I accompanied him to a posttraumatic stress disorder evaluation with a psychiatrist. We both laughed as Tim read aloud and answered some of the questions on the admitting form: “Do you ever feel like people are conspiring against you? Yes. Do you ever feel the government has you under surveillance? Um, yes.”

Tim and I spent the lion’s share of the next day on the rooftop deck of the Petit Ermitage hotel in West Hollywood, a few feet from a trio of stunning Eastern European models. The contrast between these surroundings and El Rodeo was not lost on Tim, who’d been recounting his story to me without a break for hours. As the sun set, I asked Tim about his reaction to Tripp’s interview and the Spies Like Us reference. “It definitely hurt,” Tim admitted. “It was kind of a bittersweet thing, because [my family] didn’t look at what I’d done and say, ‘You know what? Timmy’s arrived. We’re proud of Timmy.’ I didn’t hear that. But I’m all the better for it, because I realize now that those were fantasies. I’m my own hero for what I did, but I’m also a guy who put my parents and my family through hell.”

A few hours later, I left Tim alone with the Eastern European models to use the bathroom. When I returned, he was holding court in front of a captive audience, spinning a yarn that was way more original than the one he’d used on Delta Force night. And this one he told without shame, because it happened to be true. After our waiter announced last call, Tim looked at us and smiled with the same fiery glint in his eyes I remembered from the first time I met him. “Okay,” he said, “who wants to break into my house, swing on my chandelier and have a dance party?”

-

http://www.playboy.com/playground/view/tim-tracy-filmmaker-venezuela-prison