Portrait of a takedown: Venezuelan journalist ‘dismembered’ online for critical report

BY JIM WYSS

[email protected]

Within days, his email, Facebook and Twitter accounts were hacked and turned against him by a pro-government group known as N33. Highly personal messages and photographs were disgorged on the web along with a torrent of threats. His telephone and personal identification number were broadcast.

Venezuelan journalists are used to being attacked for their work. The government has shut or seized newspapers, television networks and more than 30 radio stations over the years. That has turned the Internet into a refuge for many opposition voices. But cyberspace has increasingly become an ideological battleground where shadowy vigilante groups hunt down government critics.

The pictures of armed children sparked a national debate in one of the most violent countries in the hemisphere. President Hugo Chávez suggested the CIA was involved, and authorities are investigating four women invovled in the case. But Brito said he feels like the only one being punished.

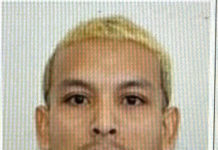

“The government says they’re investigating, but the only one who has faced any scrutiny is me,” said Brito, 26, who has been staying with family in South Florida. “They’ve dug into my private life and denigrated me, and there’s no one to turn to.”

Thirty journalists and opposition figures had their accounts hacked last year, and there have been 11 reported cases this year, said Erika Rosales with the Espacio Público, a media watchdog. Those numbers may not seem high, but these are not ordinary attacks, she said. They’re designed not only to silence but to discredit government critics. Sometimes the hackers will pose as the victim to pick fights or denounce other opposition figures. Other times, highly sensitive information is revealed. One journalist, who covers the military, had two email accounts seized that contained 15 years worth of professional contacts and emails, Rosales said.

Hacking is illegal in Venezuela and the government has prosecuted people for online crimes before. But in each of these cases nothing has been done, Rosales said.

“Everyone has lodged a complaint with the appropriate authorities but none of the cases have moved forward and nobody has been able to recover their email account,” she said.

Luis Carlos Díaz is an online journalist who gives workshops on cyber-security. While he has stayed one step ahead of the hackers, he regularly receives anonymous phone calls threatening physical harm for his work. He said Venezuela’s pro-government hackers are getting more sophisticated, using phishing scams and key-stroke logging software to seize accounts.

“This is not generalized hacking, it’s the systematic targeting of a specific sector,” he said. “And in Brito’s case they’ve not only taken him offline but dismembered his public image.”

As a freelancer, Brito had attracted more than 13,000 followers to his Twitter account. It wasn’t traditional journalism but it gave him a voice, he said. Shortly after he publicized the pictures, his account was seized and directed to a N33 site that denounced him for shoddy journalism, published his contact information and linked to personal emails and explicit pictures purportedly taken from Brito’s Gmail account.

Friends and family have been harassed “simply because of my work,” Brito said. The constant threats make him wary of going home. “They have all this personal information about me and it’s frightening because there is so much impunity in Venezuela.”

N33 began operating in 2011, targeting activists, analysts and journalists. They’ve hit some of the highest profile members of the opposition and seem to favor people like Brito, who have large Twitter followings.

“All we know is that they identify themselves as government supporters but claim they have nothing to do with the government,” said Rosales, who has tried to communicate with N33 for her research. “What we do know is that their communiqués are publicized on La Hojilla and you can’t get anymore high profile than that on national television.”

La Hojilla, or The Razorblade, is a late night talk show on state-run Venezolana de Television. Its host, Mario Silva, has found a following with his vicious, often puerile attacks on the opposition. When Brito broke the story about the armed children, La Hojilla jumped in, using the N33 cache to display pictures of Brito, calling him a “pervert” and saying he had no moral standing to be a journalist.

“There’s no way to prove they [N33] have any economic support from the government,” Díaz said. “But what we do know is that their illegal acts are celebrated and legitimized on state television … At some point you would hope the government would say ‘this is illegal’ or at the very least say ‘hey this isn’t us.’”

There are other reasons to be suspicious of the government. In April 2010, the Ministry of Communication had a swearing in ceremony for 75 “communication guerrilla commandos.” The youth, between the ages of 13 and 17, were tasked with taking on the private media and attacking anti-government messages – be it on the walls of the city or online.

At the time, Education Minister Hector Navarro described their role: “The guerrilla is everywhere and nowhere. The guerrilla needs to shoot from where they can cause the most damage.”

The government has said very little about the group since then, and Díaz suspects the program is defunct.

“Maybe this guerrilla operation failed and they’ve turned into cyber paramilitaries,” he said. “Perhaps they’re not being run by the government but they are trying to win the government’s favor.”

At first, the issue of the armed children seemed like it might get buried under Brito’s public lynching. But the case was explosive. Murals in the background of the photographs showed they were taken in the notorious Chávez stronghold of 23 de Enero, which is under the tacit control of several groups, including one called La Piedrita. It was on La Piedrita’s Facebook page that Brito found some of the images.

La Piedrita claims to be die-hard Chávez supporters, but they have lost the love of the president. On Feb. 3, Chávez said the organization and the pictures were part of a U.S. propaganda plot to hurt his reelection campaign.

“We would never incite children to violence,” Chávez said. “Nobody who is truly a revolutionary can support these things that damage the revolution. These are counterrevolutionary activities, and I assure you there is more than one member of the CIA infiltrated in those groups.”

On its website, La Piedrita claimed the pictures were altered to put guns in the youth’s hands, and then they said they were toy guns used in a street play. A spokesperson for La Piedrita, who refused to provide his name, told The Miami Herald that media distortions had turned Chávez against them. He also said it would be dangerous for this reporter to visit the neighborhood.

On March 3, the Public Ministry brought charges against two women who appear in the photograph. But Brito is convinced that nothing will come of the government’s investigation. The leader of La Piedrita, Valentín Santana, has faced an arrest warrant for years, but sometimes appears at events with government officials.

Brito is trying to rebuild his reputation – and his Twitter followers on a new account – but said he doesn’t regret publishing the story.

“Critical journalism plays an important role in forcing governments to improve,” he said. “It’s my responsibility.”

Recently, one of his sources sent him a new batch of incriminating photographs. He said he’ll publish them – when he finds a venue.

http://www.miamiherald.com